|

|

FEATURED INTERVIEW

STEPPING INTO THE SHADOWS WITH THE WHISTLER and DAN VAN NESTE

An Exclusive Radio Spirits Interview by Elizabeth McLeod

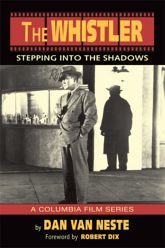

Everybody knows that The Whistler walks by night, but does everybody know that the character spawned an 8-film Columbia Pictures series? Author and researcher Dan Van Neste knows...and tells all about it…in his new book from Bear Manor Media, The Whistler – Stepping Into the Shadows: A Columbia Film Series. Covering every aspect of the series - included rare profiles of 50 Whistler filmmakers: actors, directors, writers, and technicians – Van Neste left no shadow unexplored. Fellow broadcast historian Elizabeth McLeod recently had an in-depth conversation with the author about the book and the in-depth research that backs it up.

Everybody knows that The Whistler walks by night, but does everybody know that the character spawned an 8-film Columbia Pictures series? Author and researcher Dan Van Neste knows...and tells all about it…in his new book from Bear Manor Media, The Whistler – Stepping Into the Shadows: A Columbia Film Series. Covering every aspect of the series - included rare profiles of 50 Whistler filmmakers: actors, directors, writers, and technicians – Van Neste left no shadow unexplored. Fellow broadcast historian Elizabeth McLeod recently had an in-depth conversation with the author about the book and the in-depth research that backs it up.

THE WHISTLER has long been a favorite program with old-time radio enthusiasts – its taut, suspenseful tales of fate recognized as masterpieces of the half-hour dramatic anthology format. But what many Whistler fans may not know is that the radio series made a brief, successful transition to the screen – not the television screen, but the movie screen, in a stylish series of B features produced by Columbia Pictures from 1943 to 1948. These films have only rarely been shown in recent decades, but are now undergoing a resurgence, thanks in part to the work of researcher Dan Van Neste whose new book from Bear Manor Press, The Whistler – Stepping Into the Shadows: A Columbia Film Series, takes an encyclopedic look at the production and content of these films, and examines their links to the original radio program. Broadcast historian Elizabeth McLeod recently interviewed Dan about his book – and THE WHISTLER’s forgotten movie career.

Q: How is it possible to turn an anthology radio show with no continuing characters other than the narrator into a viable movie series?

DV: A great question! All film series prior to the Whistler including - Charlie Chan, Boston Blackie, The Lone Wolf, Blondie, etc. - contained continuing characters with whom film audiences could identify with and attach to. The main characters were sympathetic heroic types. In contrast The Whistler films were anthologies with different characters in each film. Many of the Whistler protagonists were out and out villains. The main reason Columbia opted to make the series was the incredible popularity of the radio program, which by 1943 (when the first Whistler film was being planned) was a sensation on the U.S. west coast. Harry Cohn, the head of Columbia Pictures was a shrewd businessman who would go out on a limb when he was convinced a project had merit and would be popular. He obviously felt a film adaptation of the radio program had enormous potential. When he decided to do the first picture, he purchased the rights to The Whistler name; and along with Columbia B unit producer Rudolph Flothow, set in motion a plan to make the film a success. They employed Whistler creator J. Donald Wilson to provide a story and oversee the picture, signed Academy Award nominated screen veteran Richard Dix to play the lead, and assigned a talented up and coming young director, William Castle, to helm the production. The picture, entitled The Whistler, was a stunning success and became the first of 8 entries in a new Whistler series (1944-48) which famed film critic Leonard Maltin called, “one of the most unusual and one of the best mystery series of the 30’s and 40’s. . ."

Q: How closely did the Whistler films stick to the basic theme of the radio series -- the idea of a criminal's acts coming back to haunt him by a seemingly-random twist of fate?

DV: From the outset there was a conscious effort made by all involved parties at Columbia to remain faithful thematically to the radio program. This faithfulness continued through the first six Whistler pictures. All were critical successes and made a profit. For some reason producer Rudy Flothow allowed the last two Whistler films - The Thirteenth Hour (1947) and The Return of the Whistler (1948) - to veer off course in multiple ways. Both were decent movies and contained some key Whistler elements but lacked the flawed protagonists and powerfully ironic conclusions which had been the hallmark of both the radio and film series. Unsurprisingly, both proved unsuccessful.

Q: What role did the Whistler himself have in the films -- was he merely a narrator or did he occasionally appear on screen? How closely did he match the radio version of the character?

DV: The radio and film Whistlers were very similar. Both served as spooky, otherworldly narrators, introducing the story, then tying up loose ends at its conclusion. Both occasionally interrupted proceedings to inject commentary or to speak to the protagonist. There were differences however. The radio Whistler appeared more sinister and vengeful, goading his main characters, laughing at their predicaments, then meting out severe punishment with vindictive delight. He was often an active participant in his chosen tales. In contrast the filmic Whistler (who is seen only as a shadowy silhouette clothed in a trench coat and fedora) was more detached; his activities basically limited to narration and an occasional comment. Like his radio counterpart he was sinister, but not to the same degree. The films revolved around the protagonists not the Whistler character. There was one instance in the eight films where the Whistler took a more an active role in the story. That occurred in the first film, The Whistler based on a tale by J. Donald Wilson . In it the Whistler intervenes to save the flawed hero’s life on two occasions. This would not happen again.

Another interesting similarity between the radio and films was the producers’ decision not to credit the actor who played the Whistler. Eventually producers of the radio series relented and revealed the great Bill Forman as the star in 1951, but Columbia never did. In fact fans of the film series did not learn the name of the actor (Otto Forrest) who played the title character until years later. To this day Forrest remains as mysterious as the Whistler himself. My repeated efforts to find biographical material on him in archives, and major film libraries for publication in this book came up empty.

Q: What input, if any, did the Whistler's radio staff have in the production of the films? Were efforts made to ensure that the films adhered closely to the style of the radio show? How much input, if any, did individual directors such as William Castle have on the style of the films?

DV: Because there is no formal Columbia archive, (Columbia’s production files and records were apparently discarded when the studio moved from Gower Street to Burbank to join Warners in 1972) we really do not know some of the key details of preparations for production of the film series. Thus I cannot tell you if the radio staff was at all involved in the production of the Whistler pictures. What we do know (from various archives) indicates there was a strong commitment to make sure the new films adhered closely to the successful radio program both on a stylistic and substantive level. The fact that J. Donald Wilson was brought in to provide the story and oversee the first film was particularly significant. Also important was the decision to retain the essence of the Whistler character, his classic recitation, and suspenseful intro replete with the eerie 13 note Wilbur Hatch composed theme. Even more proof is found in the content of the films which capture the essential style of the radio program.

Castle and the other Whistler directors had varying degrees of influence over the finished films depending on how much enthusiasm they had for the particular projects. Contrary to popular belief all B movie directors were not studio hacks. Many cared a great deal about their films and wanted to make them the best they could be considering the severe time and budgetary constraints under which they operated. Castle was certainly one who really gave a damn. At the outset of his career he directed four of the Whistlers and wrote a portion of the script for one. His Whistler films were suspenseful, innovative-- distinguished by an action packed style, innovative use of lighting and camera angles, and utilization of a plethora of gimmicks which would later become his trademark. To his great credit he pushed every possible button to make his cut-rate productions successful and was rewarded by superlative reviews and good box office receipts. Veteran directors Lew Landers, George Sherman, and William Clemens also contributed respectable Whistler entries.

Q: For most of its run, The Whistler was heard only on the West Coast. How did the film series, which was nationally distributed, cope with this -- were efforts made to introduce the idea of the Whistler to audiences who had never heard him on the air?

DV: Although posters advertising the first film refer to the Whistler character as “Radio’s Famous Master of Mystery” apparently in an effort to introduce him to a wider audience, I doubt much more was done in that regard. The Whistler films were B movies made quickly and efficiently for the purpose of filling the bottom half of a mandatory double bill. There was little promotion of B’s no matter how good they were.

Q: Richard Dix had been a major figure in films around the end of the silent era and the beginning of the talkie period, but he had had no involvement with the Whistler radio show. How did he happen to become the actor most identified with the film series?

DV: It was the hand of fate. Perhaps the Whistler was involved? (haha). Seriously, as many of you are aware Richard Dix was a big star of the silent screen and early talkie era primarily known for heroic roles in westerns and action adventures. After a long tenure as a Paramount contract player (the studio’s highest paid star) he signed a term contract with RKO in 1930. Two years later he reached the apex of his career winning critical nods and an Oscar nomination for his charismatic portrayal of adventurer Yancy Cravat in the legendary screen adaptation of Edna Ferber’s classic western, Cimarron. He remained a top star for a few years afterward but gradually began appearing in B’s (primarily westerns). Advancing age, ill health, and a desire to expand his professional horizons prompted Dix to abandon the physically demanding western roles in the early 1940’s in favor of more sedentary projects. In 1943 he began a new phase of his career, playing the first of several overtly villainous parts as a psychotic sea captain in producer Val Lewton’s atmospheric chiller, The Ghost Ship (RKO). Harry Cohn apparently saw the latter movie while in the midst of planning the first Whistler film, and approached Dix to play the lead. Unlike many in Hollywood who had worked for Cohn, Dix liked the mogul and agreed to do the part. He was signed to star in a Whistler series after the initial movie garnered rave reviews and made Columbia a tidy profit. Dix went on to make seven of the eight Whistler films, and in the process become forever associated with them. All in all he did a remarkable job in each, playing a wide range of anti heroes from well meaning but flawed individuals, to depraved, murderous human monsters. He was particularly adept at capturing the duality of the Whistler protagonists whose kindly, amiable surface demeanor often masked wickedness. Dix bowed out of the series in 1947 due to deteriorating health and died in 1949. There is an in-depth 32 page biography of him in my book which discusses all aspects of his life and career. Mr. Dix’s actor son Robert contributed illuminating memories of his famous father for the bio and wrote the Foreword.

Q: The Whistler radio series stands up very well today in comparison to other thriller series of the time. How well do the films stand up -- are they dated, or can a contemporary audience enjoy them without having to understand the period in which they were made?

DV: First let me say I believe all who view vintage movies should be cognizant of the period in which they were made, but all in all the Whistler films holds up remarkably well. If you’re a fan of the radio program you will love them! As stated, the Whistler pictures successfully captured the essence of the radio program which combined absorbing stories, suspenseful action, and ironic, often downbeat denouements. The films also contain excellent performances from expert casts, the craftsmanship of talented writers, photographers, editors, art directors, and the expertise of gifted directors including young up and comers and seasoned veterans. Today the Whistler films are recognized by many as early examples of film noir -- a popular crime film movement of the late 1940’s and 1950’s characterized by dark downbeat themes, anti heroic lead characters, and dingy settings. The series is also of interest and importance today because of its substantive impact on film and television history. Such popular suspense film anthologies as Black Sabbath (1963), Tales From the Crypt (1972), Creepshow (1983), etc. trace their roots back to the Whistlers as do memorable television series like Alfred Hitchcock Presents, The Twilight Zone, Thriller, Night Gallery, and Tales From the Crypt.

Q: The Whistler radio program is widely available -- but the films seem quite scarce. What are the prospects for seeing them legitimately issued on DVD? Do they ever show on cable television?

DV: Six of the eight Whistler films have shown up multiple times on Turner Classic Movies. I believe they were last shown in 2009 in a day long festival. For some reason the second series entry The Mark of the Whistler (1944), and sixth, The Thirteenth Hour (1947) were not screened with the others. Several other cable channels have also broadcast one or more of the films in the last decade including the Encore Mystery Channel (now called Encore Suspense), but not nearly enough. It is surprising given the influential nature of the pictures. Even more remarkable is the fact that the series has never been released on DVD. Hopefully the publicity surrounding this book will generate new fans and interest in the pictures, prompting the powers-that-be to correct this grievous oversight. People who want to see them on television and on DVD should make their voices heard by sending written requests. In April, 2011 Sony (who owns the Columbia film library) entered into an agreement with Warners Home Entertainment to release certain films through Warners DVD on-demand program. You can request the Whistlers by contacting WarnerArchive.com.

The Whistler – Stepping Into the Shadows: A Columbia Film Series, by Dan Van Neste, is published by Bear Manor Media and is available for sale at www.RadioSpirits.com.

Copyright 2011 Radio Spirits and Elizabeth McLeod. All rights reserved.

May not be reproduced without permission.

|

|